Historical photographic processes

Thanks to developments in photographic technology in recent years,

the creation of technically perfect photographs is becoming a simple

matter, even for those with no specialist knowledge. Digital photography

can now be used very easily for purposes of information and

documentation, and traditional photography can hardly compete with it in

this area.

Of course, if we examine the potential of digital photography for

individual artistic creation, it soon becomes clear that formulaic

photo-editing programs, and the essential sameness of digital prints,

even when the photographs are of completely different types, lead to a

certain predictability in the results. The photographs are perfect, but

all very much alike.

The easier it becomes to take digital photographs and prepare them

for printing, the more likely it is that people will want to return to

the techniques of traditional photography for their creative efforts, or

to combine the techniques of digital and traditional photography,

especially when producing the final version of a photograph – in the

creation of a unique, artistic original, or in other words, in the

actual process of transferring the picture to paper.

One of the basic characteristics of traditional photography, based

on the sensitivity of silver salts to light, is the fact that the

photographer can carry out many of the processes himself, adding his own

creative touch. The final photograph can take many different forms.

Each picture is a unique original. This variety in working methods, the

utterly individual character of the result, and the fact that we are

always producing an original work, will undoubtedly enable traditional

photography to hold its own, though now in the role of an artistic

technique.

If we look abroad, we find that ‘alternative’ photographic

techniques are steadily gaining in popularity. These are in fact revived

historical techniques dating from the beginnings of photography. In the

USA, there was an increased interest in the 1980s, but this has

increased further in the last few years. Processing kits for practically

all the processes ever used are available on the market there. Although

some are rather expensive, people buy them. A particular favourite is

platinotype, despite the fact that the set of processing chemicals costs

about $130. There have been dozens of US publications on the subject,

regular creative workshops are organised and there are many articles on

the internet, where there is also a discussion group.

Old photographs have a charm of their own. They are unreproducible,

each is a unique creation, and even when several are printed from a

single negative, no two are exactly the same. A high proportion of

personal creativity goes into each photograph. Every picture is

different – produced by a different process, on different paper, with

different tonality. Photographs printed in the modern minilab, though

they are cleanly produced, free of grain and in perfect colour, are

worlds apart from carbon or platinum prints.

We know from the history of photography that “high-grade” printing

methods survived for a long time. For example, many of our photographers

continued producing oil prints and bromoil prints until the 1930s,

although gelatine silver-bromide paper – of a type which is still used

today, without any substantial changes – had long been widely available.

Why did people continue so long with those laborious, time-consuming

processes? Perhaps because their greater “malleability” brought greater

pleasure and satisfaction in the results.

Those who are interested in individually oriented creation find even

greater possibilities in historical photographic processes than in

classical photography: not only is there a range of processes (salt

process, cyanotype, platinotype, oil print etc.), but there is a choice

of methods for achieving the final result (sensitising solution, type of

paper, method of processing etc.).

In today’s conditions the historical processes most widely used are

those which involve copying a negative. Sensitising the paper for

copying is much more practicable than, for example, preparing

light-sensitive glass plates for the collodion process. This means that

the first part of the negative-positive process, i.e. the negative, has

to be achieved by other means.

The old photographic techniques all involve contact printing, so we

need a negative of the same size as the final photograph. In classical

photography, this means either photographing directly in large format,

or making a duplicate negative of the required size. Only a photographer

with a fair amount of experience and a well equipped darkroom can

handle this task.

Digital technology now makes it possible to create negatives without

a darkroom. Many believe it is precisely this fact that has contributed

to such an upsurge of interest in historical methods in the last few

years.

In any case, historical photographic techniques do not require a

conventional darkroom. The sensitive paper is prepared and processed

with an ordinary low-wattage tungsten bulb. For the exposure, an

enlarger is not necessary; a wooden contact-printing frame with glass is

all that is needed. The exposure can be made outdoors, for example on a

balcony.

With its freedom from conventional photographic technology, this

entire creative field is opening up to people with no photographic

background – all you need to do is print the negative on transparent

film, coat suitable paper with the chosen sensitive solution, make a

contact copy, and then process the picture in low-intensity artificial

light.

There are many different processes to choose from – within the range

of what is affordable, of course. If you make a pinhole camera and use

the salt process, you’ll get pictures at less cost than with classical

photography. But if you choose the higher-grade platinum process, you

may spend ten times as much.

One thing is certain: the pictures will be interesting and nice to

look at, whichever of these processes is used – even the cheapest,

cyanotype. The high proportion of handwork clearly plays a role here,

lending a touch of “artistry”.

In the Czech Republic, historical photographic processes are of

course still waiting to be discovered. The sets of chemicals needed for

processing are not yet available on the Czech market, and buying them

from the USA is probably rather expensive for the average Czech. There

is no literature in this field in Czech. Foreign books are difficult to

track down and are expensive. There is some information on the internet,

but for the moment, of course, only a few people can read English. And

of those people, not many will start trying things out for themselves –

they would have the difficult task of tracking down the chemicals and

trying everything from scratch, with only the literature to guide them.

Far better to start on the more complex processes when someone has shown

us, first hand, the methods they use and the potential difficulties. We

will be more inclined to try things out for ourselves if we see some

fine pictures at an exhibition or in a friend’s collection. For the

moment, that’s still something to look forward to.

Types of historical contact processes

1. Processes based on the light sensitivity of silver salts

The sensitive material is silver chloride and the resulting image is

formed by particles of silver. Silver chloride can be dispersed in

various types of binding agent.

The salt process (salted paper prints)

Suitable paper is coated with a solution of sodium chloride (table

salt) and then, after drying, with a solution of silver nitrate. This

produces silver chloride, which is sensitive to light. The picture is

produced directly upon exposure (contact process). After exposure, the

surplus silver nitrate and silver chloride are washed off in water, and a

thiosulphate fixer is used. The image is formed by fine particles of

silver anchored directly in the mass of the paper, without a binding

agent. Because of the large number of silver particles and the fact that

they are finely dispersed, the picture is reddish-brown in colour (as

with all other contact processes). The salt process was first used by

Fox Talbot in 1834. Salt papers were most widely used in the years

1840-1850 (alongside daguerrotypes). Most of the photographs on paper

dating from those years were produced directly by the salt process. Some

of them are toned with salts of gold or platinum and their colouring

varies – often brownish-black, blue-black or a neutral grey-black. A

gold or platinum image is not susceptible to changes due to the

surrounding atmosphere, and is notably long lasting.

For its simplicity and convenience, and especially because it is so

easy to understand, the salt process is very suitable for use in today’s

conditions. It is not as problem-free as, for example, the Van Dyke

brownprint (see below), but the knowledge that we are working just as

photographers did in the 1850s is something quite magical.

In the National Technical Museum, we have devoted a great deal of

attention to reconstructions of the salt process because this was the

process used in 1835 by the inventor of photography on paper, Fox

Talbot, for preparing his first pictures. A further advantage is the

fact that the mechanism and chemical reactions of the salt process are

so simple and straightforward that even a reasonably attentive schoolboy

can easily understand them.

The albumen process

Thin paper is laid on the surface of some salted egg white. After

drying, it is coated with a solution of silver nitrate. As in the salt

process, the image is formed by fine particles of silver, but these are

not embedded directly in the paper, but in the layer of the binding

agent of egg white which the surface of the paper is coated with. This

makes it possible to achieve a more saturated black and greater

brilliance and contrast.

The albumen process was most widely used in the years 1855-1895 –

most of the photographs dating from those years are on albumen paper.

The image, as in the case of the salt process, is reddish-brown. It is

often toned with gold or platinum. This increases its resistance to

environmental factors. But albumen photographs are almost always

yellowed in the lighter parts, because of the ageing of the binding

agent itself – egg white.

Collodion papers

Silver chloride is held in a binding medium consisting of a mixture

of collodion and camphor. Collodion is cellulose tetranitrate dissolved

in ether and alcohol. On a paper base, the binding agent containing

silver chloride (the emulsion layer) is covered with a layer of barium

sulphate with gelatine. The image is formed by fine particles of silver

in the layer of binding agent, and as with other contact processes, it

is reddish-brown. The surface may be either glossy or matt.

Collodion papers were very popular and were used from 1865 until the

1920s. Most studio portraits from that time were taken on collodion

paper. They were often toned with salts of gold or platinum.

Gelatine papers

In appearance, these are almost indistinguishable from collodion

papers, but instead of collodion, gelatine is used as the binding agent.

They were used from 1884 until the 1920s, concurrently with collodion

papers, but they were too expensive to compete with collodion. Once

again, the image was reddish-brown, and was often toned with gold or

platinum.

All the processes mentioned so far are “contact” processes, in which

the picture is produced during the exposure, and subsequent processing

merely gives it definition and stabilises it. This distinguishes them

from the other group of processes, known as “developing” processes, in

which only a faint (or even invisible) image is created during exposure,

and is developed by subsequent processing. We shall discuss some

developing processes below.

2. Processes based on the light sensitivity of iron salts

These processes use ferric salts of organic acids which, under the

action of light (its ultraviolet component), are reduced to ferrous

salts. For example, ferric oxalate is reduced to ferrous oxalate. This

ferrous oxalate is retained as a reducing agent which reduces the ions

of noble metals such as silver, platinum or palladium into a solid

metallic state, creating the picture. The sensitive solution is applied

directly to the paper, so that the picture is anchored directly in the

paper without a binding agent.

Instead of the salt of a noble metal, the cyanotype process uses

potassium hexacyanoferrate(III), which, with a ferrous salt (produced

from a ferric salt under the action of light), creates a blue pigment.

The cyanotype process

The sensitising solution contains iron ammonium citrate and potassium

hexacyanoferrate(III). Developing is done in water. Depending on the

method used, the image is created in Turnbull or Prussian (Berlin) blue.

The image is produced directly during exposure; this is therefore a

contact process. It was in use from 1842 onwards.

Cyanotype is, relatively speaking, a very simple, quick and

inexpensive process. For this reason, it is one of the first processes

tried by many of the people who are now turning to historical

photographic techniques. If the picture is toned, there are many

options. It can be toned with tea, coffee or tannin after previous

bleaching with alkali. Salts of lead or copper are also used. Depending

on the toning used, it is possible to obtain various shades of grey,

black, brown, red or yellow.

The callitype process

The sensitising solution contains ferric oxalate and silver nitrate.

The image is formed by metallic silver. During exposure, only a very

faint image is produced; this is intensified by subsequent development

in a solution of borax or sodium potassium tartrate. This is therefore a

developing process. It came into use in 1844.

The platinotype process

The sensitising solution contains ferric oxalate and potassium

chloroplatinate. A faint image is produced, and is developed in a

solution of potassium oxalate or some other organic acid salt. The image

is formed by particles of metallic platinum embedded directly in the

paper (process in use from 1873 onwards).

Platinotype is a very popular process in the USA, despite the fact

that it is, relatively speaking, quite expensive. Apparently the US

tradition plays a part here – a number of famous photographers in the

last century used this technique to create many impressive photographs,

which people come across in exhibitions, and quite naturally this

stimulates their desire to make their own platinum prints. Another

reason may be the fact that this technique produces completely unique

and valuable pieces of work, which may survive not only us, but perhaps

several generations to come, without any deterioration.

Van Dyke brownprint

The sensitising solution contains iron ammonium citrate and silver

nitrate. The image is created during exposure – a contact process. This

is followed by washing in water and fixing in thiosulphate. The image is

formed by metallic silver of a reddish-brown colour, without a binding

agent, directly in the paper. The process was in use from 1889 onwards.

The Van Dyke brownprint is another relatively simple, rapid process

which may present fewer problems than other processes. With suitable

paper, a satisfying result can be achieved on the very first attempt.

The processing of the exposed image is simple, too – no chemicals other

than fixer are required.

The process as a whole is quite inexpensive. The sensitising solution

contains just three ordinary substances. One of them is silver nitrate,

which is quite expensive, but because only a little sensitising

solution is needed to coat the paper, the process does not cost too

much. And the resulting picture looks every bit as good as, say, a

platinotype, which is considerably more complex and many times more

expensive to produce. But if we still wish to achieve the qualities of a

platinotype by this process, we can tone the finished picture with

salts of platinum or palladium, or both together. This gives a

platinum/palladium-based picture, i.e. a copy identical in quality at

about one quarter of the price of a platinotype. Of course we choose

only the really successful pictures for toning, which is likely to mean a

further saving.

The main advantage of platinotype is its durability. But if we want

to use the old processes mainly for pleasure, the advantage of unlimited

durability is probably not so essential. Although silver-based

photographs produced by contact processes are less stable than those on

modern baryta papers, our pictures will probably survive us just the

same. Although the surviving photographs on salted papers from the 1850s

have faded considerably, the images are still clearly visible and have

their own charm.

The relative affordability and advantages of the Van Dyke brownprint

have led us, at the National Technical Museum in Prague, to start with

this process as the first to be presented in our creative workshops,

“Reconstruction of Historical Photographic Processes”. These workshops

are intended for interested members of the public, and the aim is that

participants should become sufficiently familiar with the old processes

to be able to use them at home. We will provide them with the necessary

chemicals for this purpose.

3. Processes based on the light sensitivity of bichromated gelatine or gum arabic (high-quality prints)

These are based on the fact that bichromated gelatine and gum arabic

(known as “glue stock”) harden in light, so that that they no longer

swell in water and are not soluble in it. The parts of the picture which

have not been exposed to light remain water soluble and are washed away

during development in water. In the case of a pigment print, the image

is formed by pigment which is finely dispersed in the binding medium

when the sensitive layer is prepared. In the case of oil and bromoil

prints, the image is formed with colour applied subsequently to the

relief which was produced in the gelatine when the light-exposed surface

was washed in water. In this way it is possible to obtain sharp,

high-quality halftone images.

Before exposure, the paper is sensitised with a solution of potassium or ammonium dichromate.

The paper is exposed to light with a significant proportion of UV radiation, and developed in water; no fixer is used.

Pigment prints

The sensitive paper is prepared as follows: suitable paper is coated

with a layer of gelatine containing finely dispersed pigment. This may

be a pigment powder or carbon powder – in which case, it is called a

carbon print.

Before exposure, the paper is sensitised by soaking in a solution of

potassium bichromate. After drying, the paper is exposed to produce a

contact negative. The exposed paper is soaked and then pressed onto

“transfer paper” (paper coated with a layer of pure gelatine). The image

from the original paper adheres in its entirety to the transfer paper,

so that its bottom layer is now on the top. All parts of the original

gelatine with pigment which were not exposed to light (and are therefore

not hardened) can now be washed off with water. This produces an image

which has the thickest covering in the places which were exposed to the

most light, as a result of the hardening of the pigmented gelatine. In

this way, a positive is obtained from the negative. The original paper,

on which the exposure was made and from which the entire image was

detached, is then discarded.

Pigment prints, particularly carbon prints, were once very popular

among our photographers, and we often see them in exhibitions. If you

learn to prepare pigment paper yourself, you will find it is a

relatively simple and rapid process. Since inorganic pigments are very

stable, the picture is almost as durable as a platinotype.

Gum prints

The paper is coated with a solution of gum arabic with potassium

dichromate, to which watercolour or tempera paint or powder pigment has

been added. After drying, the negative is copied in sunlight, in a

contact printing frame. After exposure, the picture is only slightly

modulated. It has to be developed in cold water, which dissolves the

unexposed areas, leaving the exposed areas (the shadows in the picture).

Because of the thinness of the layer, the exposed parts reach the

surface of the paper and adhere firmly to it, so that the picture,

unlike pigment prints, does not need to be transferred. During

development in cold water, the unexposed parts are washed away, with the

colour, as far as the surface of the paper. The picture does not

require any fixing, because the chrome salt is washed away as well.

Gum printing is thus a very simple method, but in order to get good

results, we need to gain some experience. We also have to accept the

fact that the single-stage gum print described above cannot reproduce

all the halftones of the negative. With the single-stage process, there

is always a certain amount of detail missing, either in the highlights

or in the shadows – depending on how the sensitive layer is prepared,

and the choice of exposure and development times.

A picture with saturated shadows and more detailed highlights can be

obtained only by several stages of re-copying. After the first

development and drying, which provides only middle tones, the picture

has to be coated again with a sensitive solution containing less gum

arabic and colour; it is copied again and developed until the highlights

appear. After drying, it is coated again, with a solution containing

the largest amount of gum arabic and colour, and copied for a shorter

time, then developed until only the deepest shadows remain.

For a good rendition of tones, it is often necessary to make a second

and third print. Usually it is also necessary, between individual

prints, to size the paper again, because the original sizing agent is

washed off the paper during processing in water. If the paper is not

re-sized, the sensitive solution penetrates deep between the fibres of

the paper and cannot be washed out during processing, so that there is a

haze of colour even in the clearest highlights.

A multilayered gum print with well reproduced halftones is thus quite

labour intensive and cannot be prepared in one day. But even with

single-stage gum printing, it is possible to obtain perfectly good

pictures, provided we accept the limitations of the process and choose

suitable motifs, and perhaps copy only the middle tones. Fortunately,

gum printing is not, for us, the only possible technique, and negatives

in which we need a more perfect rendition of halftones can be processed

more simply – for example, by pigment printing.

Oil printing

Based on the principle that a gelatine layer sensitised with

dichromate hardens in the places where it is affected by light, so that

these parts do not swell during subsequent soaking.

After a contact print has been made, the picture is soaked, and the

places unaffected by light become swollen, while the exposed parts do

not. Thus, during soaking, a relief is created, in which the raised

areas correspond to the highlights and the hollows to the shadows. When

thick, oily colour is applied to this moist, swollen gelatine relief, it

is left adhering only to the light-exposed parts (not swollen, and

therefore forming hollows), and the more these places were exposed to

light (and therefore hardened), the greater the amount of adhering

colour. This produces a picture with all the halftones. A positive is

produced from the negative.

Colour is applied with special brushes, and more or less colour can

be applied, more or less thickly, in different places. The density and

tonality of various parts of the picture can therefore be influenced to a

significant extent. This process differs from pigment and gum printing

in that these contain colour before the contract print is made, while in

oil printing it is applied afterwards, in a chosen quantity. The

advantage is that coloured parts with which we are not satisfied can be

cleaned with petrol.

Bromoil prints

These differ from oil prints in that an ordinary photograph, i.e. a

silver bromide positive, is used for preparing a swollen-gelatine

relief. The photographic paper we use should not have an excessively

hardened gelatine layer, because this would not swell much in water.

Many types of paper on a resin coated (RC) base, and some traditional

baryta papers – provided they are not intended for glazing, and

therefore harder – are suitable.

The photograph with well defined highlights and shadows is bleached

in a solution of copper sulphate and potassium dichromate. It is then

washed, fixed, washed again, and finally dried. The dried picture is

soaked and left to swell, and is then coated with oil pigments, as in

the case of oil prints. Nowadays, instead of the traditional method of

dabbing the colour onto the picture with a fitch brush, the colour is

sometimes applied with a foam roller.

The coloured picture can be printed onto another piece of ordinary

paper. The picture can then be coloured again, and it is also possible

to create a series of prints.

The end result is just as good, whether it’s a bromoil print or an

oil print. But bromoil printing has many advantages. In particular, the

fact that it does not require a large negative, because you work

directly with an enlargement the same size as the final picture. There

is also no need to make contact prints in sunlight using a contact

printing frame. This removes the need for difficult decisions about the

necessary exposure time. Another advantage is that you can easily

influence the degree of contrast in the final picture through the choice

of the grade of photographic paper used for preparing the initial

positive. But it should be emphasised that the relative ease of

preparing the basic gelatine relief in no way relieves us of the need to

become thoroughly proficient in the next stage, the application of

colour, which requires a high degree of skill and plenty of experience.

You can’t expect successful pictures at the first attempt.

Because of their advantages, bromoil prints were very popular with

our photographers until about the 1920s, and they are often seen in

exhibitions.

Choosing the process

If you want to try a historical process yourself, it’s a good idea,

initially, to choose one of the simpler ones that doesn’t require too

much outlay. Fortunately, even with the simpler and less expensive

processes, you can obtain pictures which are just as good as with the

more demanding and costly ones. Every process has its own character and

possibilities. It’s just a matter of knowing it well and choosing the

motifs to which it is best suited.

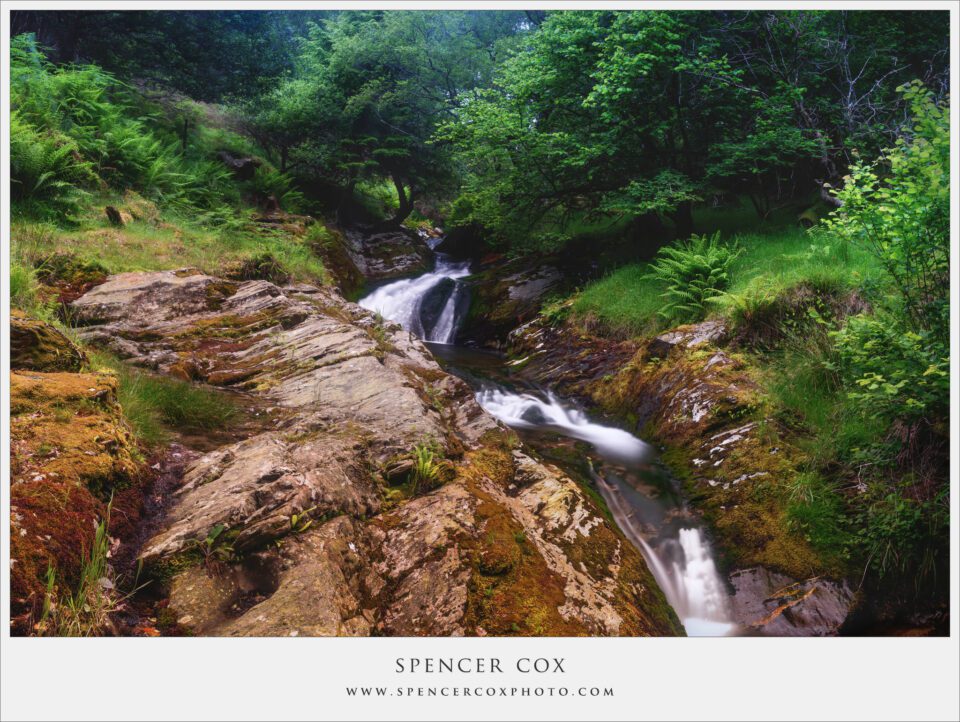

Even with the cheapest process, e.g. cyanotype, we can create very

impressive photographs. But their intense blue colour is only suited to

certain subjects – snowy or misty landscapes, for example. On the other

hand, these subjects are not suited, for example, to the salt process.

This gives a brown tonality in which snow or mist appears unnaturally

brown. On the other hand, the salt process is suited to autumn pictures

with fallen leaves.

So it’s best to choose processes which can be carried out with simple

resources and minimal experience, and to select the subject matter

accordingly. Such processes are, for example, cyanotype, the salt

process and Van Dyke brownprint.

With these processes, you obtain a picture embedded directly in the

fibres of the paper without a binding agent. The fact that the picture

is on paper without a layer of binding agent, means that it has much in

common with a lithographic print. Unlike ordinary photographs, these

pictures do not curl up in heat. If you choose suitable colours and

structures for preparing the paper, you can obtain really special,

unreproducible originals.